Telstra Small Business of the Year!

We were lucky enough to be awarded Telstra Small Business of the year (NSW) at the Telstra Business Awards 2014.

Like

In November, Elevate released its report “A student perspective! A benchmark study of students' attitudes to getting back to school in a post lockdown environment”, which drew upon surveys and interviews with close to 3000 students across the UK in order to understand how COVID-19 and school closures have impacted students’ perspectives and attitudes towards the return to school.

This week, we turn our attention to the third-biggest concern students have this academic year: managing their workload.

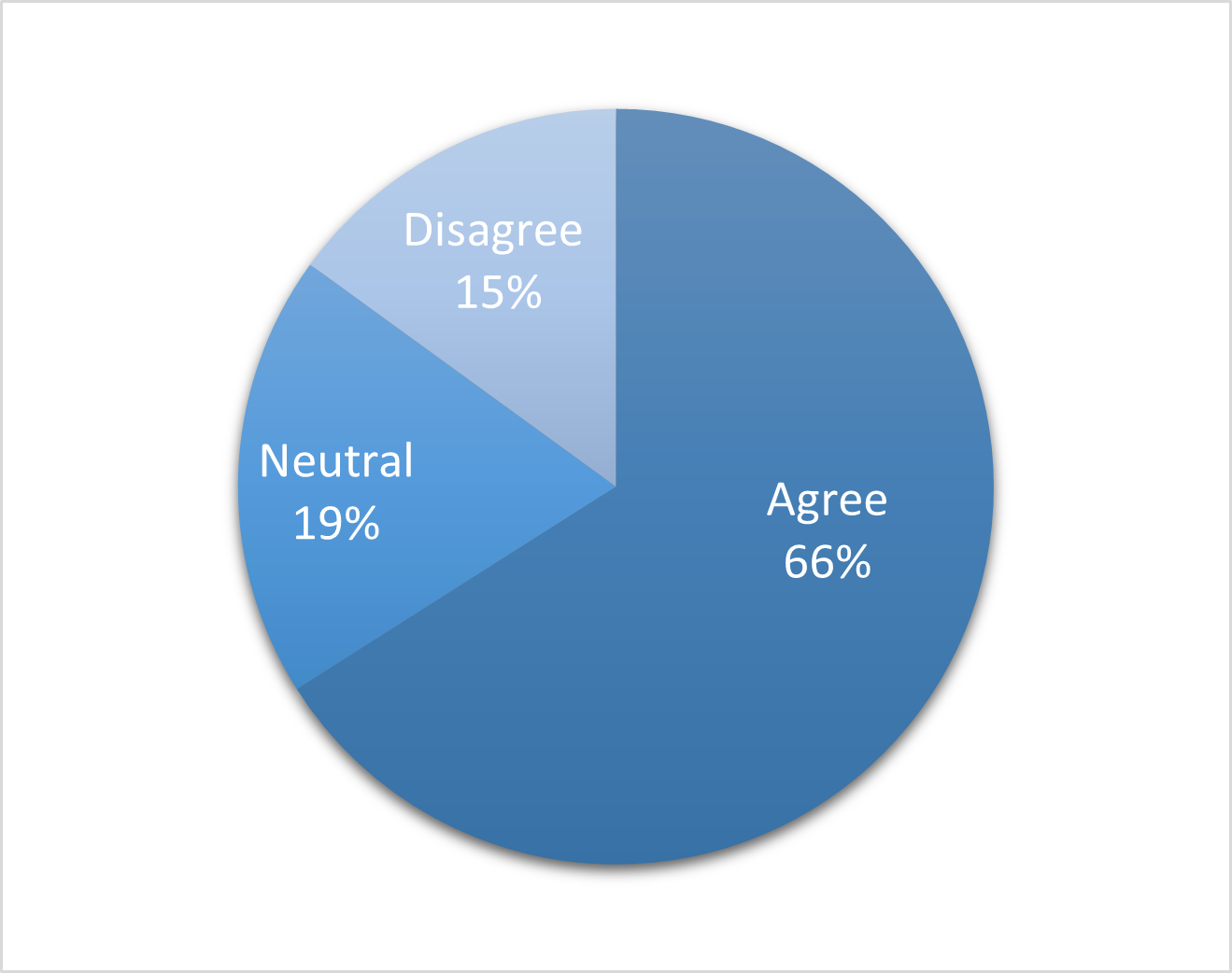

It is clear that a vast majority of students have returned for the new academic year with a significant sense of worry. Indeed, 66% of students surveyed stated they were worried about their performance this year.

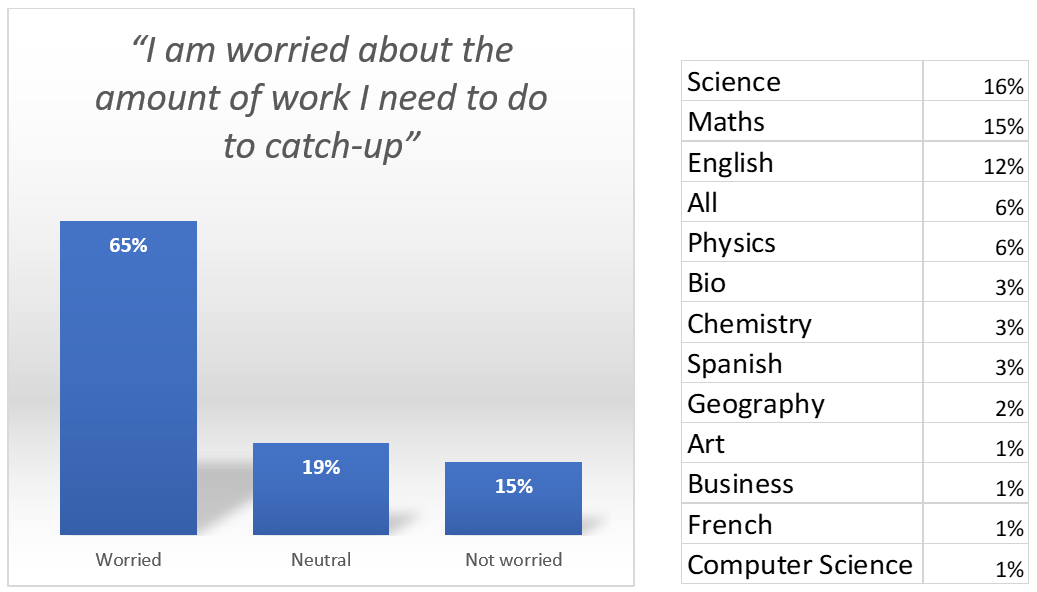

65% of students fear they will be unable to catch-up and manage a greater workload this year. 59% stated they had at least 1 subject they felt they had fallen behind in, of which the three most common subjects were Science (16%), Maths (15%) and English (12%). 6% of students felt they had fallen behind in all of their subjects.

Finally, workload was the 4th most prevalent fear for students should schools close again across the academic year, with 17% of all students stating this as their primary fear.

What does this mean for schools?

We believe there are two issues schools need to consider when it comes to workload:

What you can do

We believe there are 2 easy-to-use strategies schools can use right now to help their students catch-up and stay on top of their workload:

1. Help students to reduce re-work

One of the least efficient habits students fall into in secondary school is re-working or re-writing their notes. We have found there are 2 reasons why students tend to re-work their notes across the term:

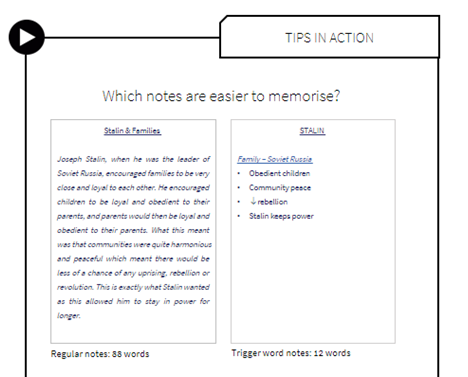

A lack of efficient note-taking skills. The most common reason students need to re-work their notes is because they make them in a format that doesn’t easily facilitate review or revision. In recent benchmarking we have conducted with schools, 34% of students made long-form notes composed of long sentences and paragraphs, trying to get as much information into their notes as is humanly possible. Generally, this is done under the mistaken belief that more information in their notes leads to more information being committed to memory. However, these students find when they come to review their notes prior to exams that long-hand notes are extremely difficult to revise and mentally organise. As a result, most students are forced to re-write their notes into smaller summaries, wasting a significant amount of time.

This problem can be easily solved by introducing students to more effective note-making strategies. In our Study Sensei and Study Skills Kick Start seminars, we introduce students to the Split Page and Cornell note taking methods. The advantage of both of these systems is that they require students to use trigger words in their notes, rather than long-winded sentences or explanations. This means students’ notes are laid out from day one in a format that is significantly easier to revise. In addition, the act of distilling their notes down to a few words, rather than simply copying out their textbook, forces students to grapple with the content and consider its meaning, increasing understanding as well as saving time.

We have found over the years that note-taking tends to be one of the meta-skills schools underemphasise with their students. In our conversations with classroom teachers, we often find an attitude of “horses for courses”, that everyone studies differently or students fall into the patterns that work best for them, and if a student uses a specific type of note-taking system, they do so because they have consciously selected it on the basis that it works for them.

Unfortunately, this is rarely the case. Studies by Jacobs (2008) and Zorn (2017) both showed superior performance and improvement from students using a system of note-taking such as the Cornell Method. The benefit of this approach has been found to be even higher for ESL students and SEN students (Alzu’bi, 2019). As such, there are clearly more effective note-taking strategies that schools should be exposing their students to.

However, exposure by itself is rarely enough. Changing or adopting a new note-taking methodology is difficult, and generally requires that students are supported through the transition through repeated practice and exposure in order to overcome the innate desire to revert back to what is known and comfortable. However, those schools who not only expose their students to alternate note-making methods, but also help guide them through the transition stand to increase student performance and confidence significantly, as occurred with one of Elevate’s client schools in Australia - John Calvin Christian College - who achieved a significant increase in school performance simply by doubling down on their students’ note-taking skills.

A misplaced emphasis on rote-learning. The second reason students spend so much time on re-work is the mistaken belief that re-writing their notes prior to an exam is actually beneficial. As was covered in Issue One of our newsletters, our benchmarking has shown that 65% of students re-write their notes prior to exams under the belief that it is the most effective way to memorise their notes and ensure long-term memory retention. As has previously been outlined, schools can reduce this re-work from students by introducing them to more efficient and effective memory techniques such as those covered in our Memory and Mnemonics seminar.

2. Peer-to-Peer Learning.

The second method for helping students to manage their workload, and catch-up if necessary, is the formation of study groups and use of peer-to-peer learning. As discussed in Issue 2 of this newsletter in regards to motivation, peer-to-peer learning has a range of benefits beyond creating mere efficiency. These include:

However, getting peer-to-peer learning to work is often easier said than done. In our experience many of the peer-to-peer learning initiatives introduced into schools fail because students don’t have adequate structures or frameworks to keep the sessions on the rails, with the result that the sessions simply degenerate into idle student chit-chat.

The peer-to-peer learning initiatives we have seen work best in schools generally have 4 shared characteristics. They are:

In the previous issue, we discussed the Rule of 5, one of the group learning frameworks we provide students with in the Finishing Line seminar as a great structure for peer-to-peer learning. The Rule of 5 is perfect for peer-to-peer learning, as it provides a very clear structure and framework for students to work within. Each student’s role is clear. Students have high levels of mutual interdependence and the task cannot proceed unless each student performs their assigned tasks, thereby preventing free-riding. Further, each task within the process has a clear deliverable, making it easy for teachers to monitor, mark and guide group progress.

If you would like to discuss any of the ideas within this blog, or the ways in which Elevate can help your students navigate the challenges of the new academic year, then don’t hesitate to contact a programme coordinator at info@elevateeducation.com or 01865 989 495.

Seminars that could help your students:

Next week: What students want! Find out the most common requests that students have for support at the moment. To subscribe to this newsletter click here.